for my grandmother, Naomi Hansen. I loved the way she talked.

She never had a couch,

certainly not a sofa.

Only the davenport:

each unnecessary syllable

another lumpy cushion.

Oh my land

we knew her mild expletives

but not her stories--

descended from Norse stoics,

raised by American gothics,

she knew how to be invisible and unmovable;

self-effacing and all-powerful--

a simple, omnipotent country girl.

You're like to lose your britches,

a sharp yank by the beltloops.

In her arms we shrunk,

dwarfed by her sturdy density,

pinned like butterflies by staccato lipsticky pecks.

That pragmatic love meant nothing more or less

than protection from the elements,

than our survival ensured at any cost.

That affection had no time for coddling.

En route to matriarch,

Naomi obeyed the 1950s:

made children with matching initials and

hand sewed prom dresses;

gave both her names away

in favor of Mother;

hosted bridge clubs and PEO and unironic wiener roasts;

collected porcelain birds,

made jello and called it salad.

Aw, heck

prone on the davenport, she dismisses us with her hand,

turns off the television--

can't hear the damn thing anyway.

I lean in to say goodbye.

She smells of the indignity

of a body outlived.

Eyes rimmed red, paler blue than ever,

her voice is stronger than the rest of her:

you sure are a heckuva good lookin' gal.

In her tiny arms I am buttressed.

Her words and I

no longer dwarfed by anything solid.

We are what's left of her.

Monday, May 23, 2011

Sunday, May 22, 2011

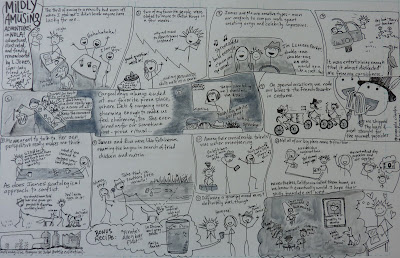

mildly amusing adventures with james and mo

still working out readability with this fancy new ink and non-looseleaf paper.

next time i'll draw bigger. promise.

next time i'll draw bigger. promise.

Thursday, February 10, 2011

remarks for louisiana teach for america alumni

for the 20th anniversary summit

One thing I learned as a special educator is that as often as not, the thing that really disabled my students was not within their own minds or bodies. They were disabled by rhetoric: by the labels, diagnoses, gossip and euphemisms that were used to describe them. And once I saw this, it wasn’t long before I realized that such disabling rhetoric targeted not only my students, but entire swaths of Americans who failed to toe various invisible lines.

I believe that the way we use language creates our reality; the way we talk about each other matters. This conviction led me, after five years in the classroom and two as a program director in SLA, to study the rhetoric of the achievement gap as a doctoral student in the LSU English department.

My favorite philosopher said that “metaphor is never innocent. It orients research and fixes results.” I think it’s an important insight for all of us in education. When we refer to teachers as being “on the front lines,” or “in the trenches,” where do students figure in those violent metaphors? If we are “racing to the top,” we’re speaking as if there is still going to be a bottom—so who might find themselves there? If we talk about poverty as if it’s a disease with measurable “risk factors,” then we shouldn’t be surprised when researchers crank out data that suggests poor kids are less capable than rich ones. Wallace Stevens would rush to remind us that “what we said of it / became a part of what it is.”

I don’t need to tell you why Louisiana is a great place to think about this stuff, because I suspect that many of you have, like me, spent hours reveling in the unexpected and powerful uses of language that abound in our state. The things that come out of my students’—not to mention my neighbors’, colleagues’ and friends’—mouths continue to make me laugh and think and imagine. And if there is a better way to talk about each other (and I know that there is) then I’m pretty convinced that we can learn it in this place.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)