some blunders and absurdities

teaching. drawing stick figures. writing some things.

Monday, May 23, 2011

untitled

She never had a couch,

certainly not a sofa.

Only the davenport:

each unnecessary syllable

another lumpy cushion.

Oh my land

we knew her mild expletives

but not her stories--

descended from Norse stoics,

raised by American gothics,

she knew how to be invisible and unmovable;

self-effacing and all-powerful--

a simple, omnipotent country girl.

You're like to lose your britches,

a sharp yank by the beltloops.

In her arms we shrunk,

dwarfed by her sturdy density,

pinned like butterflies by staccato lipsticky pecks.

That pragmatic love meant nothing more or less

than protection from the elements,

than our survival ensured at any cost.

That affection had no time for coddling.

En route to matriarch,

Naomi obeyed the 1950s:

made children with matching initials and

hand sewed prom dresses;

gave both her names away

in favor of Mother;

hosted bridge clubs and PEO and unironic wiener roasts;

collected porcelain birds,

made jello and called it salad.

Aw, heck

prone on the davenport, she dismisses us with her hand,

turns off the television--

can't hear the damn thing anyway.

I lean in to say goodbye.

She smells of the indignity

of a body outlived.

Eyes rimmed red, paler blue than ever,

her voice is stronger than the rest of her:

you sure are a heckuva good lookin' gal.

In her tiny arms I am buttressed.

Her words and I

no longer dwarfed by anything solid.

We are what's left of her.

Sunday, May 22, 2011

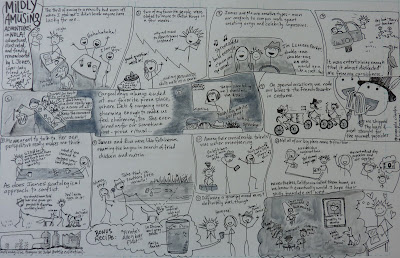

mildly amusing adventures with james and mo

next time i'll draw bigger. promise.

Thursday, February 10, 2011

remarks for louisiana teach for america alumni

Monday, October 11, 2010

thoughts on national coming out day

I taught a literature class at Louisiana State University this summer. As I chose readings and wrote my syllabus, I had the same two things on my mind that I always consider when planning a class: first, what are the most enriching and potentially transformative texts I can put in front of students? And second, how can I be utterly certain that I am not pushing a personal or political agenda? I guess all the talk of the liberal academy has got under my skin, probably because it’s not nonsense. For this reason, I hesitated before assigning Gloria Naylor’s story, “The Two.” It’s a beautiful, thoughtful and powerful text, but it is also clearly about the persecution of lesbians by everyone from outwardly violent young men to “harmless” old gossiping women.

When I began teaching, in 2000, I was even more paranoid. I wouldn’t say I tried to conceal the fact that I am a lesbian-- that would be a pretty impossible task; the dyke runs very deep in me, for some reason--but I came pretty close. I bought a wardrobe that was entirely uncharacteristic: long skirts, women’s shoes, blouses. I grew my hair longer than it had been in decades and I wore a little bit of makeup. All of these things were not only new but deeply uncomfortable; I felt more like a schoolmarmish drag queen than anything. But I was teaching high school in the South, and I had my notions. On some level I feared violence, but much, much more than that I feared ridicule and contempt. My personal life was out of bounds in classroom discussion—no anecdotes about my weekend, for instance, lest I accidentally say “we” and invite questions from always-curious students. I am ashamed to say that once, I even told a flat-out lie.

An amazing ninth grader with an apparently underdeveloped gaydar, Terence, had taken a liking to me; he wanted to go with me to work out afterschool, to take me to the movies, all sweet stuff that I of course declined. He said “you must have a boyfriend, huh?” What I should have said is “no” and then reminded him yet again of teacher-student boundaries. Instead, I said “yes,” in that kind of lie that feels like nothing more than convenient shorthand: rather than tell you the complex truth, let me tell you a simpler lie that will get us to the same understanding. It never works out that way, of course. He asked questions about my boyfriend’s job, hobbies, looks, favorite foods…and I answered all of his questions accurately--about my girlfriend’s brother. I never told Chris that he was my imaginary boyfriend that school year. Or that a kid named Terence knew everything about him short of his social security number.

One day she asked me. Point blank: “Miss Jones. You gay?”

A few weeks later, on the final exam, I asked them to name a text that had been most important to them and explain its importance. 75% of the class chose “The Two” and the overwhelming explanation was the same: it made them realize that when they called someone a “fag” or a “dyke” or speculated recklessly about another person’s sexuality, they were paving the way for violence against gay people. This was, let me remind you, Louisiana State University, which has got to be one of the more conservative state schools around. I mean, I regularly have to explain to students why the Bible might not be the best or the only source of evidence for their persuasive essays. Sierra said this:

I believe with all of my heart that violence more often than not begins in language. And I also believe, accept, and ask pardon for the fact that my language is violent more often than I realize. How else could words work, if they didn't violently reduce the infinite nuance of the world down to single syllables? Richard Wright discovered as a young man that language could be used as a weapon. He was right, of course; and we too often deploy that weapon only to claim innocence, or love, or righteousness. These fights we fight with words, they defile the sacredness of our relation to one another. And we have, we always have, the option to reject them outright, to refuse our consent. I don’t know what it would look like, and as I search for a way to wrap up this ramble, I am desperately trying to envision it--if only in the name of a satisfying conclusion. But those tend to be violent as well, cropping as they do the complexity of things. So today I sit with complexity, I retrace my steps and missteps in language and in teaching, I give thanks for the lessons so many people have taught me, and I hope like hell that we are all learning something here.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

Saturday, June 13, 2009

a speech to new teachers

Hello.

Nine years ago, when I was sitting where you're sitting right now, I felt like a huge fraud. After a week of icebreakers and workshops and job fairs and getting lost on the way to…well, everywhere, after seeing how impressive and confident everyone around me looked, I felt mediocre, unprepared, and dreadfully homesick. It almost made it worse that my new colleagues and I had been personally thanked by a string of important people simply for our presence in their state, as if we were superheroes who represented the last hope of some crumbling Gotham. Maybe it was just that being from a long line of Yankees, I didn't know how to handle a warm welcome back then. But I think there was more to it, to my discomfort with this undeserved hero's welcome we received. I don't know if any of you have a similar feeling right now, but if you do, I'd like to suggest that it might actually a good thing.

So, doubt and guilt hovered over me throughout institute, even as I worked through half the night trying to become the pedagogical superhero I thought the people back in Baton Rouge expected me to be. It grew when I returned to Baton Rouge and learned that my English degree would be put to use teaching special education science. And when I showed up to Glen Oaks High School with my beautiful handmade posters and meticulous lesson plans to learn that I had neither classroom nor students, I thought that maybe I had been found out, maybe this was a sign from the universe, a sign that I ought to just go home. I collected such signs from the universe throughout my first month teaching. I did what was asked of me, sitting in the back of another teacher's classroom and making sure the SPED kids didn't disrupt class. And it was about a month in to this most self-indulgent of existences that I was finally able to set aside those doubts. Trying to ease my mind, my principal finally leveled with me: "Look. These kids can't learn science. We'd be lucky if they learned to spell science. But, the law says we have to let them be in the room."

Thinking about what it meant to be on the receiving end of messages like that for the better part of one's life led to my first moment of clarity as a teacher. My current insecurities notwithstanding, I realized that from the moment I was born, I had been receiving messages about how the world saw me: everyone assumed that I would succeed, that I could learn quickly and well, that I would go to college, that I deserved to live a long and reasonably comfortable life.

And from the moment they were born, the students I was supposed to be teaching had also received messages about how the world saw them: they were uneducable, a drain on society, a problem needing to be fixed; they learned that the world would be more surprised to see them graduate from high school than to hear that they had died young and violently or been sent to prison.

Here's what I learned in that moment: this is not about me. And I will say it to you: this is not about you. No matter how many community leaders shake your hand and treat you like a hero, do not be lulled into believing that this is about you. No matter how many signs seem to point to "you suck, go home kid," resist this tendency to see the world in terms of yourself.

Because if this is about you, then every insult—and there will be many—will eat at you, will be an affront, rather than a symptom of what you're working to alleviate. If this is about you, you will become bitter, because you will expect a reward for your hard work. You will come to resent Louisiana and Teach For America and public education for asking you to do work that you will see as thankless and fruitless. Faced with failure, you will protect your ego by looking for explanations outside yourself. You might blame the system, your principal, your roommates, your program director, your textbook, the broken copy machine—anything but you. You may even take up the most convenient and insidious mantra of the frustrated new teacher by blaming parents who "just don't value education." Worst of all, thinking in this way, you will come to resent your students, for, focused on your own discomfort and discouragement, you will see them as nothing more than an obstacle standing between you and your success.

Take a moment now, please, to revel in the absurdity of that. Tell yourself that this will never be you.

In the coming months, remember this moment and let it shield you from ever subscribing to those poisonous and destructive myths. Accept now that you will sometimes fail, that you will even more often feel like a failure, and that this is nobody's fault. Moreover, fixing it is nobody's job but yours. And you must fix it, however you can and no matter how hard that is to do.

Another thing I learned from my principal that day was that my kids were right to resist their teachers, to mistrust me. If—having spent the majority of their lives in a system that told them repeatedly that they were impossibly stupid—they still enjoyed school, still obeyed the people who sent them those messages, well I think that would have been fairly stupid. Their resistance was so far from personal insult, I realized; it was, in fact, evidence of their brilliance. I realized that it would be my job to tell them this a thousand times, and more importantly, to devise ways to let them see it for themselves, and while we were at it, to prove to anyone who doubted them that they were indeed the proud owners of brilliant young minds; to demonstrate that they could learn science; that they deserved to learn science; and that to fail to teach them science--or anything else, for any reason—was, simply put, a crime.

****

Okay: so if this were a movie, we would now cut to a musical montage with scenes of me jumping around the front of the classroom using revolutionary teaching methods, while students fall, slowly but surely, under my spell, until they finally realize that I am the best thing that has ever happened to them. The scene would culminate at a ceremony in which I am named Best Teacher Ever by the President of the United States, and my students and I would, in slow-motion, jump up and down and hug each other with tears in our eyes, and the credits would roll and the audience would cheer.

But here's the thing about that: I hate those movies. I really do. For one thing, they're all about the glorious teacher and her heroic efforts, and as I've already told you: this can not be about us. I feel like half the disappointments of new teachers can be traced back to dreams borne of those movies, to a desire to be Jaime Escalante or to inspire a Dead Poets' Society. I imagine teachers across the country standing at the front of their classrooms daydreaming about whether they'd rather be played by Michelle Pfeiffer or Hillary Swank, and being disappointed when all that happens is that their students learn.

Worse yet, I can't stand the fact that the students are the antagonists in these movies. The teachers save them from themselves and their families and their communities and their cultures. They teach the unteachable children, tame the dangerous minds, redeem the irredeemable thugs. They're not teachers; they're demigods—and what a dangerous set of assumptions that breeds. It's a set of assumptions that brushes up against the old tales of White Man's Burden far too closely for me to want anything to do with it—in that movie world, students and their families are hopeless, aimless, worthless until a charismatic outsider comes along, savior-style, and gives their pitiful lives meaning.

So please, let's take another moment right now to revel in the absurdity of such arrogance. Bathe yourself in disbelief that we ever swallowed such stuff.

And now choose: for the next two years, you can either indulge your own Stand and Deliver fantasy, or you can become a great teacher. But know this: the two are incompatible. A great teacher would make a lousy movie star. He's relentlessly in the background. When you walk into his classroom, he's not in front, jumping up on the desk with barbaric yawps or shredding textbooks. He's not blowing children's' minds. No: his students are in front, blowing his mind. He orchestrates, he choreographs, he works insane hours behind the scenes, but he never, ever stars in that show. We all need to learn, and relearn, and cultivate that humility. This is the Zen of teaching: it is not about me.

So to return to this moment, to your vivid present and my nine years' past, it's worth noting that all this is a pretty big shift from our recent lives as college students. Those four years were entirely about us—I was bathed in praise for my brilliant essays, you for your incisive comments in class, she for her meticulous lab work. That constant recognition can be a great source of energy. And it's one you can no longer count on. I don't know whether I expected to be celebrated and praised as a teacher, but I certainly wasn't, and this forced me to learn a second lesson: that the communities of South Louisiana have far more to offer to me than I could ever offer them. That Louisiana doesn't need saving, by me or anybody. On the contrary, it can save you if you let it. During what will perhaps be the hardest thing you do in your life—it remains so in mine—this state can give you the energy, joy, and reward you will so desperately need.

Now, you'll meet lots of people who haven't let that happen, and you'll come to recognize them almost instantly. They like to focus on how this place differs from whatever better places they've lived or been. They're quick to remind anyone who will listen that there's no good movie theater here, that the folks in the coffee shops don't know how to make a real macchiato, that we're #12 on the Forbes list of America's most violent cities, 2nd in new cases of HIV, that over 1/4 of adults in BR lack literacy skills, and that the Mexican food here is mediocre at best. Oh--and that the air smells funny sometimes because of the paper mill across the river. They seem to revel in the fact that their students lose relatives to violence at a staggering rate, as if this is somehow evidence of their own street cred as a quote-unquote "inner city teacher." It's just like in the movies.

Now, you'd be wrong not to notice these things, and I'm certainly not asking you to don rose-colored glasses during your time here. The mistake that these unhappy people make is that they notice only these things, and that's a recipe for hopelessness and cynicism, neither of which makes a very good teacher. Louisiana is magic, and I genuinely hope you'll be open to that magic. You won't always see it unless you look for it, and you won't look for it if you fall prey to the illusion that you are here to save this state. Don't get me wrong: our public education system is a source of unutterable injustice, and I am glad that you have come to join the thousands of others who are determined to change that, who have already made progress in that direction. But that doesn't erase the fact that this place is magic, and that to be welcomed to this place, as we all have been—whether it was at birth or a just few days ago—is a gift. The communities in which we teach and live are vibrant places in which poverty is only one factor, one that we too often let blind us to the many others: Sunday afternoons, when every other front porch is crowded with people. Tailgating at Southern and LSU where strangers will ply you with the best food you've ever tasted.

Shoot—once, up on Plank Road, a hard-looking guy in a custom car noticed me admiring his rims, and then saw my out of state plates. He rolled down his window at the red light and said, "Welcome to the Dirty South. Do you like cookies?" He dug in the grocery bag next to him, opened a bag of Chips Ahoy, ate one, and passed a handful out the window to me. I mean, that just does not happen where I'm from, and that's what I revel in about this place. That's also what I think about whenever those closed-off-to-magic people talk about the menacing ghettos in which they star in their imaginary movies.

Church congregations greet heathenish strangers like me without reserve. Festivals celebrate everything worth celebrating and plenty that you might think isn't. My neighbors know my name and turn my water back on when I forget to pay my bill. Tangerine trees drop fruit while my family back home shovels snow. Just yesterday, my students groaned when I told them there were only five minutes left in class—they wanted to learn more about Gandhi—because here, as everywhere, kids are born to learn.

Please notice these things. Seek out your students when you're not teaching. Watch them be kids. Explore your town. Speak to people. Look deeply at this place that has welcomed you, and work to understand just what it is you've been offered. Don't presume to know about it; but do undertake to learn about it.

*****

As for the rest of my first year teaching, it was more the stuff of dull memoir than music montage. We did succeed. I screwed up a lot. I felt tired all the time. I often felt angry and frustrated. I laughed like a twelve-year old more often than I had since I was a twelve-year-old. I loved my students so much it hurts my heart to even say it out loud. By the end of the year, they outscored the general ed kids on the science portion of the standardized test.

And as vindicated as I felt on their behalf, I can't say that it did much for them. It might have, but in the scheme of things, the science portion of standardized test was just a miniscule step towards the kind of vindication they really deserved. In subsequent years we took many more little steps, and I hope that those steps added up to something—I choose to believe that they did, but I also know that I need to do more this year, and next year, and the year after that. And I will tell you this: I have never been named teacher of the year, and Hollywood has yet to seek the rights to my story. I do keep a collection of nice notes from my program director, and my mom tells me she's proud of me. But lacking much else in the way of awards and honors, I am instead energized by what I keep learning. I came here, as I suspect many of you do, already knowing about hard work, but not understanding much beyond that. What I'm learning, and what empowers me more than anything else—what I hope you learn, because it will empower you—is humility, is how to be a gracious guest in a phenomenal community. Once you learn this—and perhaps you already have—you will be freed from the doubt you might be feeling right now, from the need for recognition or thanks, from the burden of preconceived notions about the kids you teach and their families. Then, you will be ready to become a great teacher. You will also see that two years from now you will not be finished with what you've just started, but you will be fortified to continue with more skill, more passion and more joy.

So I was right, nine years ago, to think that it didn't make sense for me to be thanked for coming here. And if it doesn't quite sit right with you either, then I'd say you're on the right track. Perhaps you already sense that South Louisiana will give you more than you could ever hope to give it. I hope that you accept those gifts. Your students will shine beyond all the stereotypes and self-fulfilling prophesies, because I know you will expect them to, and I trust that you will put your hard work in behind the scenes and shine the spotlight on them. In the end, when you stand where I now stand, looking at a new group of talented individuals sitting where you now sit, you will feel as lucky as I do to have been invited to this place and to be entrusted with its children. You will know, as I do, that our work as corps members and alumni of Teach For America, our work of guiding students toward significant academic gains, is nothing like heroism—it is merely the rent, to borrow from Shirley Chisholm, that we each pay for the privilege of living in this incredible place.

Thank you.

Tuesday, March 24, 2009

the plank in my eye

I paused in this half-bent-over position, confused. I hadn't seen any tree branch between my face and the ground, but sure enough, there had clearly been one directly in the path of my eyeball. After thinking about this for a moment, I stood up. I heard a tiny =s n a p != and realized that it was the sound of the little branch breaking off the little tree, still in my eye. It was hard for me to believe that I had a tiny tree branch sticking out of my eye, BUT I DID! It had slid in between my eyeball and my eye socket. When I pulled it out, still too struck by the million-to-one odds of this happening to be upset, I SWEAR TO YOU that I could feel the tiny branch gently tickle the inside of my eye socket. It was perhaps the strangest sensation I've ever felt. I'm not sure that anything other than my eyeball has ever touched the inside of my eye socket before. I was reassured to discover that the sensation was not remotely erotic, because the idea of reproducing that situation on purpose is a little upsetting.

After that I was fine, but as we walked, I couldn't stop thinking about how weird it was that I had stood in the street for a moment with a tree branch poking out of my eye. I wish I could have seen myself.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

freshman angst

So, freshman year (sorry...."your first year of college") can suck. It can suck really quite badly, for reasons that I don’t need to outline here because you are living them. It can also, of course, be wonderful and amazing and magical. I don’t mean to dismiss that; it’s just that at this point in the semester, the suckiness tends to outweigh the magicalness by a significant amount.

Some of you are probably finding that college is much harder than you expected it to be. This makes me mad because it tells me that educators—maybe on the high school end, maybe on the college end, maybe both—aren’t doing their jobs well. Forgive me for saying it—I don’t mean to insult anyone—but having taught high school for a few years, I saw how much the average high school falls short from giving students what they need and deserve. I’ll bet that many of you not only got straight As and Bs in high school, but got them without breaking a sweat. Now you’re taking college chemistry or calculus or whatever and you feel like you’re drowning just to pass with a D. You probably turned in first drafts for As in high school, and now you’re having to write and rewrite just to barely get a C. That’s not right, because it means that you weren’t pushed to work to your potential in high school. It means you were allowed to skate by, and led to expect that education was easy.

The same was true for me. I had never worked very hard in school, and suddenly, in my freshman year, I was getting up early to study and staying up late to write papers and still barely making it in some of my classes. It got better—much better; better to the point of being more enjoyable than it was painful. The same will be true for you. Depending on how hard the semester has been for you, that might sound completely hollow and meaningless, but I hope you’ll take my word for it. It will get easier. I need to add ONE qualification to that: while my roommates let off stress by enjoying various intoxicating crops and beverages, I studied. It didn’t get better for my roommates. (This is not a “say no to drugs” message, I just don’t want you to come back in two years and tell me “it didn’t get better” in between hiccups as I recoil from the smell of Night Train on your breath. My former roommates are, for the most part, successful and happy people now. They’re just not college graduates). The point is: barring poor prioritizing or errors in judgment on your part, it will get better.

Another thing that still baffles me a little: you all are not a normal class. You weren’t specially selected or anything, but somehow your group ended up being different from the usual freshman writing class in some interesting ways. What I’ve seen in your writing is a kind of humor and style and playfulness that is, in my opinion, the mark of solid intellect. I’m not saying your essays were mind-blowing all the time, but I am saying that even when they were weak, they still had that mark. I don’t think I got a single one of what most writing instructors complain about, the dry and lifeless 5-paragraph essay that is grammatically flawless but says absolutely nothing. Your writing—and the mind that produced it—has substance. If I were in charge of admissions at a university, that would be my #1 criteria because that is what’s going to make your college education meaningful. All the skills--like how to use a semicolon or how to…jeez, I can’t even think of an example for chemistry…all I remember is making soap in the lab--can be learned by anyone. To be able to use the skills in a meaningful way, that’s something that (in my opinion), you either know or you don’t, and you all are in the first category.

Here’s the rub: that quality—intellect—is also going to make your college education challenging and perhaps painful at times. It took me a very long time to realize this, and even longer to accept it, but learning is painful. I don’t mean just painfully boring—it hurts. It’s like growing pains. Your worldview is expanding, your perspective is stretching, your capacity for abstract thinking (which, by the way, isn’t fully developed until age 30!) is being pushed beyond its old boundaries. It’s just like pre-season workouts for whatever sport you might’ve played: they hurt, and they suck, they give you blisters and make you throw up and you can’t wait for them to be over. That’s what the first semester of freshman year is like. You’re getting in shape for college, and it’s punishing. And though it will get better, it should never be totally comfortable. After a really good class, I’ve realized, I’m often exhausted. I think that’s because learning something really meaningful does a couple of things. It shakes your foundation by showing you that something you’d always taken for granted is much, much more complicated than you ever realized, and it sets off a chain reaction in your brain. Here’s a very basic example from my freshman year. In a class called “semiotics” we started by talking about how language is basically arbitrary. The only reason that the letters “t-r-e-e” mean the wooden, leafy thing outside the window is because we all agree on it. If everyone who spoke English agreed to it, we could start calling that thing “e-r-t” and it work work every bit as well as “tree.” The more I thought about it, the more I realized how many things that we take for granted—I mean, ever since I was a kid I just assumed that t-r-e-e was somehow logically linked to a tree—were just made up, arbitrary, random. It’s fascinating and it’s exciting, but if you really think about it, it also hurts your brain and shakes up your worldview a little bit.

That, my friends, is why not everybody wants a college education. Not everybody is willing to submit their worldview to questioning and shaking up and expansion through torturous exercises. Watching the cartoon network and drinking milkshakes is much more comfortable. If this were easy, everyone would do it. It’s not, so here we are, suffering and sweating it out at the end of the semester.

And of course, life doesn’t stop in order to give you four years to focus on expanding your knowledge. If only it did. Lots of things happen that change your life and threaten to push education out of its spot at the top of your priority list. It’s a struggle to keep it there; it’s never as simple as just reminding yourself that “education is important.” But the fact is, for folks like you, it is. Because you’re the folks who are going to (I know, I know, here she goes with “the children are our future”) go back into high schools and say “it’s not good enough” to give kids busywork and make them take standardized tests once a year. And, well, you might want to straighten out a really messed up economy, do something about climate change, and bring about world peace. Most of all, though, you’re going to need to find a niche for yourself, a role that you want to play in the world, one that you find fulfilling. My grandfather was a typist for 35 years—for eight hours a day, five days a week, for 35 years, he typed. He made decent money and got a great retirement plan and was a happy, wonderful man who found his fulfillment outside of work. The thing is, if he’d had what you all have—the intellectual substance I’ve seen in your writing--he would have gone postal in that job. I’m not saying he was dumb. He wasn’t; he was simply more of an action-guy than a thinker. Y’all may be action people, too, but you’re definitely thinkers. Although you could quit school any time and get a job as a typist, I would guess that you wouldn’t find a whole lot of fulfillment there. I suspect that in order to be satisfied, you need something that is available to college graduates.

All of that is to say, don’t give up. Ask for help. When you screw up, be nice to yourself about it. And most of all, remember that no matter what happens, three weeks from today you will be able to lie on the couch, watch cartoon network, and drink milkshakes all day.

I can’t believe you’re still reading. You should go study for finals or something.

Very best,

Laura

Sunday, September 7, 2008

some lessons i learned during hurricane gustav

1. There is a limit to the number of household repairs that can be made with candle wax and bandannas.

2. It is best to let fighting dogs figure things out for themselves.

3. A laptop battery runs out at the climax of any given film.

4. The desire for free ice and water is a metaphysical desire; FEMA is the unattainable Other.

5. There is such a thing as battery-powered fans. Elsewhere.

6. The kindness-and-togetherness-during-trying-times thing runs out after 3 hot days without power.*

7. Everybody loves Boggle.

8. Canola oil works great as starter fluid.**

9. Curfew is for real.

10. Generators are much louder than the people who use them (sitting inside with the TV blaring) probably realize.

*this rule, fortunately, does not apply in Spanish Town, where kindness and togetherness are virtually bottomless.

**thanks to DeWitt Brinson for this lesson.

Thursday, August 7, 2008

for matt and sara's wedding

Beyond What

Alice Walker

We reach for destinies beyond

what we have come to know

and in the romantic hush

of promises

perceive each

the other's life

as known mystery.

Shared. But inviolate.

No melting. No squeezing

into One.

We swing our eyes around

as well as side to side

to see the world.

To choose, renounce,

this, or that --

call it a council between equals

call it love.

I love this poem for the way it departs from one convention of weddings. There is a moment in most ceremonies that leaves me a little mournful: the one when it's pronounced that two amazing individuals, each of whom I love separately, have become One. It makes it seem as if love's ultimate effect is to reduce by half the number of wonderful people in the world, and I'm pretty sure that we can't spare them. I prefer to think of it as a pooling of resources; a collaboration that will allow each of you to better reach for destinies beyond what we have come to know.

Today, in my mind, rather than melting, rather than squeezing into one, your vow is to forever amplify one another's unique capacity to live well, to engender beauty, to nurture justice, to generate love. Thinking of it this way allows me to celebrate without reserve this most inspiring and joyful council between equals. My wish is that the destinies for which you together reach will enrich your own lives and spirits and immensely as they already do ours, you beautiful two.

Wednesday, August 6, 2008

big bang

u r nowhere close 2 Forgiven

unfolding your message

like the map it is not,

i translate:

u r hopelessly lost.

unforgiven and aimless,

i'll buck against the straps of

your grudge.

as i chafe, you'll bruise;

i'll be

sorrier.

rampantly

sorrier.

i'll stomp

every wrong i've done

into the shit and mud and straw.

i'll snap and bound and

vault like a brahma;

u r still just a jackass.

i'll rage

against this stasis.

bellowing

my humanity,

i'll absolve

my own damn self.

here:

is my guilt,

cast off, undigested, shining

pearl of

you-were-right.

forgive me

or don't--

your anger is tiny

against stars.

it is a firefly

in a universe

born of mistakes.

you

are right

and i

am infinite.

uncapped

maybe a little too syrupy-sweet & sentimental...if you have a sensitive gag reflex that is triggered by Precious Moments figurines and the like, proceed with caution.

Amongst the faded school portraits, off-center snapshots and blurred Polaroids in our family album is a series of noticeably sharper photos of me, my brother, and my uncle Randy in the forest. I don’t know if it’s my imagination, but just as the pictures are more vivid, so are my memories of the moments they captured. Evidence, perhaps, against the belief that snapping a picture steals a bit of the moment or the subject; maybe it’s the opposite. Maybe it enhances the moment and the subject’s memory of it, but the memory is only as sharp as the picture. That would explain why my memories of my teen years are so fuzzy. And why celebrities don’t seem to get Alzheimer’s.

Randy was by far my youngest uncle, and I adored him. At some point, he and his girlfriend were amateur photographers—as everyone is required to be at some point in their young lives—and they asked my brother and me to be their subjects. They envisioned some sort of heartwarming children-in-nature photo shoot, I suppose, fall colors being very much in sync with the palette of late-‘70s fashion. I knew nothing of fashion or hackneyed themes, but the proposition of a walk in the forest with Randy was worth jumping at. He let us go as slow as we wanted, never seeming to mind when we’d squat over a patch of clover to look for one with four leaves, or become otherwise fascinated and still. He never forced us to talk, and when he did speak, it was in a soft voice, using words that I could understand. Too, he talked to me and my brother separately. Most adults treated us as a unit, asking us questions that seemed to require a single answer from the both of us. On our walks, I could count on Randy walking beside me for a ways, saying one or two things, not minding when I only nodded in response.

I wore my poofy orange coat, my beloved orange coat. Ryan and Randy were in navy blue—baseball- and poofy- style, respectively. We walked along the train tracks, my favorite route. I couldn’t tell you what the trees looked like, or the sunlight filtering through them, or the sky: I kept my eyes on the ground. That’s where the magic is, especially in a

At some point, Randy stopped our wanderings and sat us down under an oak tree. He posed us, backs against the tree, next to each other, closer than we normally cared to be. My eyes were on the ground, still; my fingers raked through the dry grass and oak-tree debris. I picked up an acorn, cupped it in my palm, and looked at the acorn cap in my other hand. Here's the epiphany: I realized that they were supposed to be together; that they used to be together; that each acorn had one, single cap that would fit it perfectly. The cap in my fingers didn’t fit the acorn in my palm. I tried another, and another, and, unfazed, others. I knew, somewhere in my mind, that I would try every cap on every acorn in Rhode Island until I found the one that fit. I kept my back against the tree and my shoulder touching Ryan’s--as we had been posed--but I had sunken into fascination.

At some point, my brother craned his neck to see what I was doing. He watched for a moment before twisting back around (his back still against the tree, his shoulder touching mine), picking up an acorn and some caps. He put them in his lap to be examined and sorted; I continued my piles on the ground.

All the while, there was a faint noise in the background, one that barely entered my consciousness. “Laurie, would you look up for just a minute? Into the camera?—Okay, um, Ryan? You too, buddy. Look over there!” Randy’s voice remained gentle as he repeated the request thousands of times and I remained hunched over, oblivious. Eventually tuning in, I might have been a little annoyed with this distraction; I don’t remember. I looked up, but my hands continued to feel the ground for another cap, to try it on the acorn, to add it to the misfit pile. It must not have been long before my gaze was pulled back to the ground, and I’d hear Randy’s voice again. It was like being at the dentist—you can never open your mouth wide enough, long enough, for him. You want to, and you feel bad that he has to constantly remind you, but somehow you’ve lost a little bit of control over your mouth, which keeps involuntarily closing. So did my head keep drifting down, my eyes insisting on getting a better view of the task at hand.

The pictures are beautiful—rich colors, sharp details—much more professional than anything else in our photo album. Our small figures at the base of the tree are vivid orange and deep blue, and it’s nice to be able to see that sunlight-filtered-by-branches thing that I had overlooked. They look kind of like the picture that comes in a frame when you buy it. It’s pretty, but the people are anonymous. The fact that these photos, these records of my first realization about the world, don’t contain my face is my own fault, of course. Personally, I think it’s perfect: this image of the tops of our little heads, as uncapped as acorns.

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

burning buildings

Been trying to write this for years...finally got a first draft. Sure it needs lots of revision, and equally sure my memory has embellished some details and glossed over others.

You covered my mouth and forced me to listen. The crackling sounds from the other room defied explanation: crackling so loud that we could hear it through the thick, century-old walls. You and I crouched by the door to listen more closely. We crouched the way my brother and I used to, at the top of the stairs, listening to our parents argue. I can’t imagine what you and I were thinking in the moment between hearing the sound and realizing what it was, but I don’t think we realized that we were each going to lose the resolve that had brought us to this impasse.

Sitting in the back room with you, I was exasperated. It was your roommate’s bedroom; an odd place for us to be, I guess. I had probably refused to go into yours; to be fair, maybe you refused to invite me. I’d grown used to your opacity and wasn’t trying to figure out what you might have been thinking. I knew that this was going to be our last conversation. I knew that you weren’t going to let it happen any easier than you’d let anything else happen. You were being deliberately obtuse (so I called it. I believe you termed it “inquisitive”): changing the subject, twisting words, and generally trying to stretch things out by denying me any possibility of closure. Closure. Another word that made me realize what a psychobabbling American I was. Still, that’s what I wanted, and that’s what, among other things, you withheld. When you asked me to listen for a strange sound in the next room, I thought it was another ruse.

“Seriously. Do you hear that crackling sound?”

“Shut up. Please just shut up a minute, for fuck’s sake, and let me do this.” Or something over-dramatic like that.

“Jesus, Laura! Just listen!”

I don’t know how long we listened, crouching at that door, before opening it to see the fire. We must have exclaimed something, probably obscene, upon seeing it, but I remember only the sight of it: the couch on fire looked unreal. The division between couch and flame was so clear, so well-defined, it was like a kid’s drawing. It looked exactly like you would expect a couch on fire to look. You don’t think things like that will look ordinary. You’d think the actual sight of them would be so dramatic, so new, that your preconceived mental pictures of them would be blown away. Mine weren’t. The couch was on fire, and I saw no visions in the flames. Just flames.

I don’t remember getting past the fire and out the door. Standing there in the dark, you talked like a maniac about the fire brigade. Even at that point, I was detached enough to note the amusing difference between your English and mine. I’d never said the word “brigade” in all my life, probably never heard it spoken, either. You hated it when I called attention to your way of saying things, yet you felt entitled to compare my speech patterns, repeatedly, to those of the characters on Beverly Hills 90210.

“Listen! Say that again, Laura. She sounds just like Brenda! Say it again!” All Americans sounded alike to you, you loved to say, as you asked me to repeat my pronunciation of “neither” or of “shut the hell up.” You didn’t intend to make me feel like a trained monkey, of course. Besides, I’ve never been one to turn down a bit of attention. But it seemed to happen most frequently whenever I tried to say anything remotely serious, and so it was one of the reasons that you were getting dumped that evening.

All of this was, of course, beside the point as you said “fire brigade” repeatedly. Even that--your infuriating way of derailing serious conversations, a defense so impenetrable that I couldn’t even call attention to it without getting mocked--was burning away.

“Okay. Fuck. Fire brigade. Jaysis. Got to call fire brigade. Fire. Brigade…fuck…fuck! Alex passed out! Fire bri—fuckin’ hell! I’ll go call. You get her. Ah, fuck!

What happened at this point is the part I can’t figure out how to tell. It makes me miss you, because you told it well. You found a way to tell it that didn’t leave me feeling ridiculous. My version makes me ridiculous in two ways: first, for being such a complete lackey that I didn’t even question your absurd division of labor: “I’ll go dial a phone number, you go into a burning house and drag a drunk person out of it.” Are you kidding? I like to think that I would have gone in without orders from your highness, but I’ll never know. So I just feel stupid for being so obedient. Ridiculous, also, because really, who has the gall to tell a story about themselves running into a burning building? It’s like saying, “Throw me a parade! I’m a fuckin’ hero!” And that breaks the hero’s rules of recognition somehow. This idea of heroism, the one that we’ve been groomed to crave since Odysseus sneaks into the telling of every story in some way, I think. I don’t know what to do with it in this one, because while I, like most of us, have always dreamt of doing something like pushing a toddler out of the way of a bus, or taking a bullet for a president we respect, or running into a burning building to pull out a drunk girl, I also know that one of the rules is that people don’t tell their own stories. Those tales are supposed to be picked up by a blind bard or something, sung through the ages, sung in the third person. So it’s you who ought to be telling this story, really. Maybe you are. You’ve been out of earshot for over a decade now, so I wouldn't know. Still, if you were, I don't think the story would be bursting out of my memory so insistently and with such disregard for the rules of its telling. Maybe you’ve forgotten all about it. Or maybe I’m the victor, here, and my prize is writing its history to suit me: a non-transferable prize from a dubious victory. Lovely. A story that insists upon being told by a teller whose fate is to come off ridiculous. Sing in me, muse.

Here’s how you told it: “So I come back from the neighbor’s and there’s Laura, black with soot, coughing like a bollocks. Next to her is Alex, stark naked, lying in the road, legs spread, pissed out of her mind. No idea what was happening. Nearly died and the eejit kept telling Laura to go back in for her coat. Jaysis, Alex.”

At this point, if Alex was in the room, you’d hit her, and she’d look sheepish. Still, you couldn’t describe what it was like inside the house (you gallant dialer of telephones, you), and I never told you. So that's what's left to be done.

In the moments during which you were saying and I was thinking about the word “brigade,” the fire spread to the curtains and, I really think, the walls. It truly looked like the walls were on fire, and I guess that’s not unreasonable, but it’s hard to imagine it being true. It’s not like a couch on fire; I had never thought to form a mental picture of what walls on fire might look like. The stairs were not yet burning as I climbed them, or I very well might not have gone up. There were no flames upstairs, but the smoke was unbelievable—another thing I had never thought to imagine. People describe smoke as “acrid.” It’s more than that. I mean, breathing this smoke was like breathing maple syrup. It was thick and so sweet I gagged. It had texture in my nose and mouth, like something I could grab hold of. I remember being shocked mostly by the sweetness of it.

As a little kid, I used to dip my finger in cocoa powder while I waited for my hot chocolate to heat up. Once, I put a spoonful of the powder in my mouth. It choked me as I involuntarily inhaled some of it; it was so overly sweet it burned. I panicked and spit what wasn’t already stuck to my teeth and tongue into the garbage. Breathing the smoke was surprisingly similar to that, except there was no spitting out to be done.

At the top of the stairs I half-lunged towards the bed and ended up crawling the rest of the way. I couldn’t see anything up there. I hit the bed where I thought Alex would be. I couldn’t form any words—I kept trying to say her name and only managed the first syllable and some coughing. When my hand found her, I pulled at her arms and tried to roll her over, onto the floor. She didn’t stir at first, and when she did, she shook me off like I was her mother waking her up for the first day of school. She was incredibly stubborn and oblivious, which doesn’t surprise you, I’m sure. I tried a few more times until, exhausted from coughing up sweet smoke and bile, I stopped, fell back to the ground, and tried to think. This is one moment that I can remember with total clarity: I felt sure that I had no more than a few seconds left before I would pass out. Then maybe the fire brigade would get both of us out, but maybe not. I decided I had enough time to try to get Alex once more, and if she still wouldn’t budge, I would have to leave without her. I never told either of you that part; that I had made up my mind to leave her in there and save myself. How would a thing like that sound?

This is where the adrenalin kicks in, and memory fails. I remember Alex groping for the window, through which a toddler could maybe have squeezed, and both of us ultimately getting out: me with clothes and face stained by smoke; her with nakedness not very well disguised by the thin layer of dark gray that coated her entire body. Stumbling out of the house, I remember thinking that I was probably burned, that my skin was probably peeling off in horrible ways. I was terrified by the idea of spending the rest of my life scarred and disfigured. Then I thought for a minute that I still might die—only now it would be in a hospital, half my body covered in gauze stuck to bloody tissue where skin used to be, taking insane amounts of morphine intravenously. I tried to steel myself for the pain that would wash over me once the shock wore off, and I looked for reaction in the faces of the gathered onlookers. I think I asked someone for a mirror, which must have sounded bizarre.

When people ask me whether I believe in God, the view in that mirror—intact, unscathed—is one of the moments that come to mind.

We stood there and watched the house burn: it collapsed in on itself. Did you write something on Alex’s stomach with your finger, wiping away the soot to spell out “pissed” or “whore”? I might have imagined that. She asked a fireman for a light, giggling with a fag dangling from her lips. I thought it was kind of pitiful, but I laughed—probably just for the sake of laughing. I remember looking at the stars and laughing hard, standing next to the truck on the slant of the road.

The firemen—brigade—had arrived before the adjoining houses were badly damaged, but yours was a ruin. The outer walls were intact up to the first story, but the second story was gone. The stairs were mostly still there, but they led to nothing but dark sky. Everything inside was black, crackled-looking, like it had been given a very bad faux finish by a creatively stifled housewife. I found my glasses. Only one lens was shattered and I considered wearing them for the remaining good lens. You talked me out of it and I learned to get by without seeing very well.

How could I, after all that, go through with dumping you? You were homeless, and your only money had been in the cupboard (which you called the press), protected by nothing but a rubber band. You called yourself lots of unkind names for not having kept it in a safer place, and I wondered if you had ever heard of a bank—and if you had, what charming name you might have for such a place.

When I told you, a few days later, that I had been trying to break up with you that night, you said this: clearly, the fairies had intervened. They burned the house in order to keep us together. You nearly convinced me. You also nearly convinced me that we should not only get married, but have a cowboy-themed wedding. I guess I was exhausted, too tired to argue or resist, and so went along with it for a while. This is the part I can’t tell, the part where fatigue seemed to lead to something real. Something that still won’t entirely leave me alone, that makes me feel like I lost my bard, like I’m doomed to shout my own pointless story into empty space for all time. Maybe it was the fucking fairies. I don’t know. Whatever it was, it was no match for the expired visa that sent me home. After that, it wasn’t long before I dumped you over the phone.

.:.

If there is an opposite to “running into a burning building” it must be “breaking up over the phone.” These acts would work well as prototypes for heroism and cowardice, respectively, the two extremes of a spectrum. You pointed that out, in fact, during our last conversation. Not in so many words, but however you said it, you were right.

See, here’s the thing: it's not a matter of being a hero or not. To call a person that, to expect oneself to be that, is a fallacy. Odysseus wins the war and defeats monsters only to come home and slaughter the unarmed suitors in an unfair fight. Heroism isn't a personality trait like being outgoing or thoughtful; it’s not something that you consistently are. Maybe you feel like it for an instant, a moment, an occasion that you happen to rise to, followed by another occasion to rise to or not, then another, then another. Nobody is heroic at every opportunity, and anybody can get lucky by choosing the right moment in a million, the one that people might notice and remember. I guess I didn’t realize that in my old dreams of parades and keys to the city. I would have been thrilled to know that, one day, I would run into a burning building. I would feel vindicated, in a way, like in a single deed I held undeniable proof of a simple fact that I wanted people to recognize: that I was a decent person. It’s clear to me now, though, that this version of heroism is kind of a sham—or at least that it’s the easier of the two options. The harder option, the one at which I regularly fail, is to rise to the occasion of each day, to live it with kindness and integrity and patience. And to let go of the desire to be recognized for it. I know people who do that, and they astound me. You and I really ought to find ourselves some people like that, love.

Saturday, January 12, 2008

dialect poem

wouldn't cover your toes in the bed,

wool shrunken

in numbing northatlantic saltwater,

fibers condensed into platitudes,

stiffened into the shapes

of my slumbering missionary ancestors.

this puritan tongue

knows Better,

chastens with euphemism,

distills to etiquette,

absolves itself of filth and fluid,

thanking Death when he kindly stops.

this language is no quilt.

it's a veil.

it's lipless:

wrap your mouth around

its

brittle as eggshell

words;

hold them there.

this language

enacts

the limits of vocabulary,

leaves depths

unuttered.

my people can

stretch silence across oceans.

my father's language

is no quilt,

no comfort--

merely a foil

for the universal

quiet.

Friday, September 14, 2007

some lusty haikus and tankas

your living room--and I

know it is dirty.

In my mind, you arch your back

into sunlight and dust motes.

Listening to you

explain imaginary

numbers like sweet, rich

gossip: write an equation

for my cells that call your name.

Your lower lip begs,

without pout, to be bitten.

I will grant its wish.

Quick: hand me a lamp.

I'll rub. Tonight I feel like

I could conjure you.

Your buckled elbows

relinquish your body to

gravity; you're pulled

into me, and I exhale--

at last, I am close enough.

Monday, August 13, 2007

this house

| A kind of miracle. I may never pay it off; But as long as I can scrape to make the note, we’ll never drift: never be at someone else’s mercy. A single mom is expected to raise her kids without a yard, sharing bedrooms. Mine will not suffer for their parent’s mistakes. I promised myself that when he left. They have new clothes, a fridge that's almost always full; we go out to dinner sometimes. They take piano lessons. They'll never want for anything. I will keep this promise. The hours are long; but I can work at home. They don’t have to be alone, wear keys around their necks, wake themselves up. I can still be here when they really need me. I put band-aids on their cuts, hold them when they cry, take care of them. | A filthy cage. She works all day for the money to keep it, worries all night that it won't be enough. The filth builds. These walls will fall in on us one day. Her glassy eyes, her slack jaw. Hunched over the keyboard, she sends me outside, or to my room. I want to talk to her, So I sit on this patch of carpet Under her desk, listening to her type. Wearing cheap clothes and eating cereal with the black and white label: it's embarrassing. She wasted money on that old piano, when I just want nice clothes; I want brand name food. All she does is work. I think she suffers from being alone all the time. Mornings, she screams up the stairs, like she’s too weak to climb them. I sit under her desk. Her knees press my shoulder. I listen to the keys click overhead. Once, I cut myself on purpose so she would bend down to me. |

scary poem (i'm no killer)

Execution-style killings:

shocking, yet common enough

to be named.

A style:

distinct, familiar.

Homestyle

Country style

Family style

Execution style.

We know these killings.

The shock is layered:

Incomprehension covers

recognition.

No foreign war,

no act of God, corrupt government

or brilliant sociopath--

a simple act

of someone made in his image.

No lesson beneath the horror,

no benefit to hindsight--

only the act.

Only an urge, unchecked.

A choice.

Today

I choose differently.

There are many days ahead.

It's a heavy weight

I lift with a story:

galvanized community,

surviving angel,

wake up call,

turning point.

I can shoulder narrative.

The act, encased in tales

of angels, morals, scholarships:

We process.

We distill knowing's burden.

How else could I face you,

knowing we share the same dark impulse?

A naked urge to destroy

comes to us

bundled with empathy,

hunger,

loneliness;

inhaled with our first breath of world.

Were they born for this act?

Or did they bend to impulse,

momentarily weak?

It could happen to anyone.

I'm not afraid of dying this way.

It's killing I dread.

"I want justice. They took three angels away from their families but one angel survived so the story could get told."

Thursday, August 2, 2007

teaching, killing words, and castrating tongues

Anna West describes the same problem in our age of state standards and standardized tests in a poem that speaks for itself, beginning with the title: "Battle for the Board of Ed

So this issue isn't new; perhaps it's one of the rare things about English that hasn't changed from Woolf's world to ours? The accents and diction and even punctuation have changed, but through it all, education remains at odds with powerful, artful language. That's pretty remarkable, really. Tests are often blamed, but we all know that the problem is more complex than that. It's a truism in anthropology that the act of observing a thing changes it. Perhaps it's become a truism in education that the teaching of language dries it up and hollows it out. It's frustrating to imagine that we've known about this problem for nearly a century but haven't made a dent in it.As a teacher, it's downright painful to think that I'm harming what I love most (students and language). Perhaps we're asking kids to write expressively and powerfully even as we're undermining their ability to do just that. No wonder so many of them are fed up, frustrated and totally resistant to school.

Not much that we've done since 1937 seems to have altered this, so what do we do next as we try to build a system that lives up to its promises? Can it be done by individual teachers in the current system (and if so, how do we enable more teachers to do it) or is it impossible without a radical overhaul? How do we educate in a way that enlivens and empowers? I don't want to kill words, and I'd like to have nothing to do with castrating tongues.

Tuesday, July 31, 2007

Tuesday, July 24, 2007

terrorist fist jab

The Teen Center is what I’ve talked about all summer when people ask questions that make me feel idle. I phrase it as if I had more ownership in the process than I really do—emotionally, I own it, but logistically, I’ve been an enthusiastic spectator at best. “What are you doing with all your free time?” “We’re opening a teen center—we’re going to paint it when I get back.” As if I were part of any meaningful “we” in the process. I wasn’t.

For the first three days of the painting, I stayed home. I had decent excuses—I hadn’t been formally informed of the location or the work hours, and I had left messages, I told myself. Truth is, I knew where the place was—I’d driven past it to check it out in my early enthusiasm—and it’s easy enough to drop by, wearing grubby clothes, and pick up a paintbrush. I was nervous, when it came down to it. Here’s a very close-knit group of 15 or so kids and their 2 or 3 mentors, and though I’ve been on the periphery of their work for a couple of years—in the audience at their open mics, teaching at a school that one of them attends, only that single kid, Kareem, even knew who I was. I hate being on the periphery of something so good—wondering if they see me, if they wonder who I am and why I’m so interested in what they’re doing, fearing that they’ll see me as some creepy adult who skulks about their projects. So I stayed home for the first three days, waiting to be held accountable for my promise to help by somebody other than my conscience.

On Thursday, I forced myself to go in around noon. I knew Natalie, the adult mentor who was working with them, and was relieved to have her show me around. The place looked great: they’d painted a couple of rooms and had 4 or 5 left to tackle, and they were into it: painting, dancing, laughing, looking like a postcard of student investment. It would’ve been a dream come true if I hadn’t been so self-conscious. I knew most of these kids by face—I could tell you about their poetry after a year of monthly open mics—but they clearly had no idea who I was. Most of them didn’t make eye contact at all, being too busy with the painting (or dancing), and those who did were polite in the way I’ve learned kids are when they’re casing an adult—not sure whether I was trustworthy, whether I had power over them and whether I would use it to hold them back, whether they would ever see me again. I might’ve been a supervisor, a senator’s aide, a local reporter, a safety inspector, a well-meaning but clueless small time philanthropist. I knew more than I probably should have known about their foibles and their personal dramas from their poetry and irrationally, it hurt that they were so coolly cordial and formal when I tried to break the ice. It hurt, even though it was exactly right, exactly what they should do, exactly what anybody would do.

Being socially awkward to begin with, this awkward situation would have terrified me if I hadn’t had a job to pour myself into. After a few hours of work, the adults began to crack the jokes that I’ve become accustomed to: “Shoot! Take a break, wouldya? This woman’s working like she wants a promotion” and the well-meaning but humiliating compliments: “Boy, this girl’s a hard worker. Kids, you need to take a lesson from her.” I try to make jokes with the kids, who respond by saying, “huh?” This always happens, and I can never figure out whether it’s my northern accent, my tendency to mumble when I’m being sarcastic, or the fact that my sense of humor is totally at odds with theirs (aka I'm old). I tell Erica that she should paint a pole with a candy-cane stripe and get “huh?” I tell James that his paint-spattered face is a good look for him, and he says, “huh?” There’s nothing worse than being forced to repeat a lame joke, nothing that can make a person want more to curl up and disappear. Worst-case scenario, I’ll just paint my ass off for a few days and then forget about the whole thing. But I want to know these kids. I want to be involved in this thing, I want to be a part of it, I want to help them make this happen, I believe in this, and in them, so strongly that it would make them uncomfortable if they knew.

I cracked lame jokes with Kareem, hoping he wouldn’t be embarrassed to be talked to by the weird adult in the room. Being as gracious and big-hearted as he is, that probably never occurred to him. On the second day, Sarah started asking me impertinent questions, much to my relief. Having taught hhigh school for five years, I had become really good at giving evasive answers that were always good for a laugh. At least I could show her that I wasn’t uncomfortable with her—well, I was uncomfortable, but not for the reasons I was expected to be. We talked about the color of my prom dress if I were still allowed to go to prom and she said I was crazy. I think one of the things that has me hooked on working with kids this age is the feeling of first getting a smile out of them. You have to work your butt off and be incredibly patient with most kids in order to get them to set aside their cool veneer and crack a smile, but when it finally happens, you feel a momentary triumph that’s incomparable. The beginning of the school year has always been my best time of year for that very reason: I’m on top of my game as I navigate the thin line between laying down the law and coaxing out a genuine, non-sarcastic or mocking, smile.

Before teaching, I wanted to be involved with kids somehow. I tried volunteering a couple of times, but after one awkward day of being left out on the periphery with barely any eye contact from the kids I was working with, I’d quit. I didn’t realize that it was a process that took time and effort, or that this is as it should be. I also didn’t realize that the kids that make you work hardest for it are the ones that will rock your world and make strained weeks seem like small change for such a phenomenal reward.

On the third day, Diana shows up. She’s clearly an old soul, a wise and soft spoken and immensely powerful young woman whom the other kids, whether overtly or not, look to a lot. To be cliché about it: a quiet leader. She’s incredibly polite, and very reserved, and very charismatic. She says, “Excuse me” a lot, in the place where most kids would just yell out your name to get your attention. She doesn’t call people by their name, something I can identify with—for a long time, and still with people who are older than me, it sometimes feels like I’m being overly familiar to call people by their name. More accurately, it would feel overly familiar to call them by their first name, and overly formal to call them by their last, so I resort to things like “excuse me.” She’s also the girl that seems to know exactly how much playing is okay: she’ll mess with her friends and then stop at the exact moment when an adult might think about reprimanding her. She’s the girl that hangs out towards the back of the room, and when I ask for someone to paint the bathrooms or collect paintbrushes that need to be cleaned, gives other people a chance to volunteer. After a pause long enough to determine that no one wants to do it, she steps up and quietly volunteers—I don’t know if she realizes that this will prompt the rest of the group to volunteer more willingly to do whatever I ask them to do next, but it does. They don’t do what I ask them to do—I still have to stay for an extra half an hour rinsing out paintbrushes—but they do volunteer to do it. That’s a step. Sarah decides to paint a little; this is the first time I’ve seen her do much in the way of work, and Kat points it out to me. “No way. Sarah, I love you!” pops out of my mouth, which I would normally never say for fear of making a kid feel awkward (or, being honest, embarrassing myself). “I love you too, Ms. Laura. Now get over here and help me.”

Also on the third day, Aisha, a girl who writes incredible poems, was upset. I knew very well that she didn’t want to talk to me (the weird adult) about it, but I couldn’t let her stand there without saying something. We went through the routine of me asking if she was okay and her being as polite as it’s possible to be when you’re pissed off and the wrong person is trying to comfort you, and I left it alone. I feel like the outcome of this kind of interaction could go one of two ways: either she’ll make a mental note that I care and will warm up to me later, or she’ll tell her friends that I’m trying to get in her business and that I’m creepy. Much as I dread the latter, I know that I’d never forgive an adult who knew I was upset and didn’t try to help me out when I was her age, so I have to take the risk.

Fourth day: The adult who's supposed to be in charge is MIA, again. She hasn’t come back, in fact, since leaving minutes after I showed up on my first day. I realize I’m supposed to be supervising but am totally ineffective at it. I let the kids know, sort of, what needs to be done and then let them do what they choose to do. Some work, some don't. It irritates me more each day that this happens, and that Natalie isn’t here to be the bad cop, but I know that taskmaster/teacher mode would be totally contrary to the spirit of this place, so my only tool is the occasional sarcastic cracks. Besides, the fact is that, in between long breaks to argue about whose school is best and fight over the last bag of Cool Ranch Doritos, the work is somehow getting done. Erica, in whom I’d confided on day two that I didn’t have a clue about painting, seems to be following me around. She works next to me all morning and has started laughing at my stupid jokes; she’s even countering my pointless anecdotes about my childhood with pointless anecdotes about her own. Nice. She and Trina are jokingly pole-dancing on the pole they’d painted a couple of days ago. As I walk by, genuinely embarrassed, I shield my eyes and they laugh. I let slip that I finished the Harry Potter book the day before and Trina tells me to shut up. “Oh—I’m so sorry—I didn’t meant to say that—I just meant—don’t tell me what happens!” It feels good to laugh at her; she’s embarrassed. It feels good not to be the only one who’s embarrassed. She goes on to tell me the three parts that have made her cry so far. I feel relief when I find myself wishing that she’d stop talking to me so much so we could get back to work. I hold up a paintbrush in the direction of a few kids eating chips. Sarah leaps up and says, “I got it. For you, Ms. Laura. You’re my girl. She’s my girl. I got it.”

No way.

The bus comes and takes most of the kids home at 4:30. I’m annoyed at having to wash the brushes, yet again. I’m even more annoyed when a group of five more kids emerge from their upstairs slacking-off room at 5:00, just as I’m ready to leave. Now I have to wait until they all get picked up. James is taking Diana and Sarah, but Aisha is still waiting for her mom, and I’m pissed off that she didn’t get on the bus. Instead, she’s calling her mom, her sister, her little brother, her uncle, her mom again, her sister again, trying to arrange to be picked up. I’m mad that she doesn’t get that I can’t go home after my long day until she gets off safely. “You can go,” she says.

“No, I can’t.” I counter. “Tomorrow, you need to get on the bus, got it?”

I know she just rolled her eyes. I can feel it through the back of my head.

We wait; James and the girls keep Aisha company so she won’t be left alone and awkward with an adult.

“You know, I can give you a ride, Aisha.” I say. She demures. She doesn’t want me to go out of my way. I can tell she wants to just get home and wouldn’t mind riding with me, and this emboldens me. I feel stupid that it took me half an hour to figure out that she just needed me to offer, that her mom wasn’t really “on her way.” “Come on. Call your mom and tell her you’ve got a ride. Let’s get out of here. I’m tired.”

I think—but I could be wrong—that she’s immensely relieved. We’ve solved the problem and we’re gone. As I walk out the door, Diana adjusts her bags to free up a hand. I can tell she’s going to shake my hand goodbye. She gets the wrong hand free, and after a moment of indecision, she puts her fist out to me. I tap it with mine.